This online exhibition was produced by OBORO, a centre dedicated to the production and presentation of art, contemporary practices and new media.

From March 15 to May 14, 2021

See documentation here: oboro.net/en/node/6285

Curatorial Essay

What has happened?

I don’t share personal things online; here is something I am sharing. This exhibition is the result of an invitation to curate an online show for OBORO. Throughout the pandemic, many artist friends have shared their creative works and personal social media posts, impacting my own processing of events. Difficult emotions resonated because of the pandemic and everything around it, including the Black Lives Matter movement to protest against police brutality, and the rise in racism towards Asian communities around the world. As I write this curatorial text, I reflect on what has happened since the World Health Organization declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic (March 11, 2020) and Quebec’s premier announced the first lockdown in Montreal (March 12, 2020). With few exceptions, we now experience what Italy warned us was coming in the early days of the pandemic. Italy then is our present and future.

Togetherness

Since March 2020, I have read articles about how the global pandemic would touch us personally and how, with social distancing measures implemented globally, we would seek being together, getting close to others. I saw these claims with suspicion. I rolled my eyes, thinking how wonderful it would be if this pandemic does shake us to the bones, makes us see the Other with empathy, solidarity, and above all with respect, so that we could stare eye-to-eye, knowing we are equal. Equal, not only in the living-vulnerable sense the coronavirus reminded us of, but also equal in the subjective sense, where I see the Other as I see myself, as a subject of speech with the capacity to think and to act. I thought about how proximity and distance between individuals and communities occupied my mind during my PhD. When I was writing my dissertation, I examined two artworks, Mariela Yeregui’s Proxemics and Alfredo Salomón’s Infinite Justice, where the encounter with the Other was troubled, and the idea of togetherness was challenged. As I read hopeful thoughts about how we would come together as societies, I had a theory: we would continue to be close to the objects and subjects we are already close to, while keeping at bay the bodies that we imagine far and therefore keep afar (here, I’m inspired by Sara Ahmed’s orientations).

I believe that while the pandemic has reminded us of the importance of being close to other people, it has not led us, individually or socially, to reflect on the people we are not close to. My wish was that the pandemic would incite reflection on social interactions where otherness affects the closeness and separateness between people. To me, the pandemic evoked the familiarity and strangeness of not being able to connect with others. This is the exhibition framework.

On Fissure

One of my main concerns about curating an online show was dealing with quarantine fatigue. For those of us working remotely—likely the audience of this show—online work and interaction are not a choice. When we have the choice, we disengage. As such, I decided to curate a show that was personal. The works selected engage with feelings I have experienced because of isolation, reduced physical activity, and the hopeless sense of “I cannots” in my daily activities (Sara Ahmed’s “I cannots”). Fissure is the common theme. With the pandemic, all sorts of things fractured or broke, including personal relations and a sense of control over our lives.

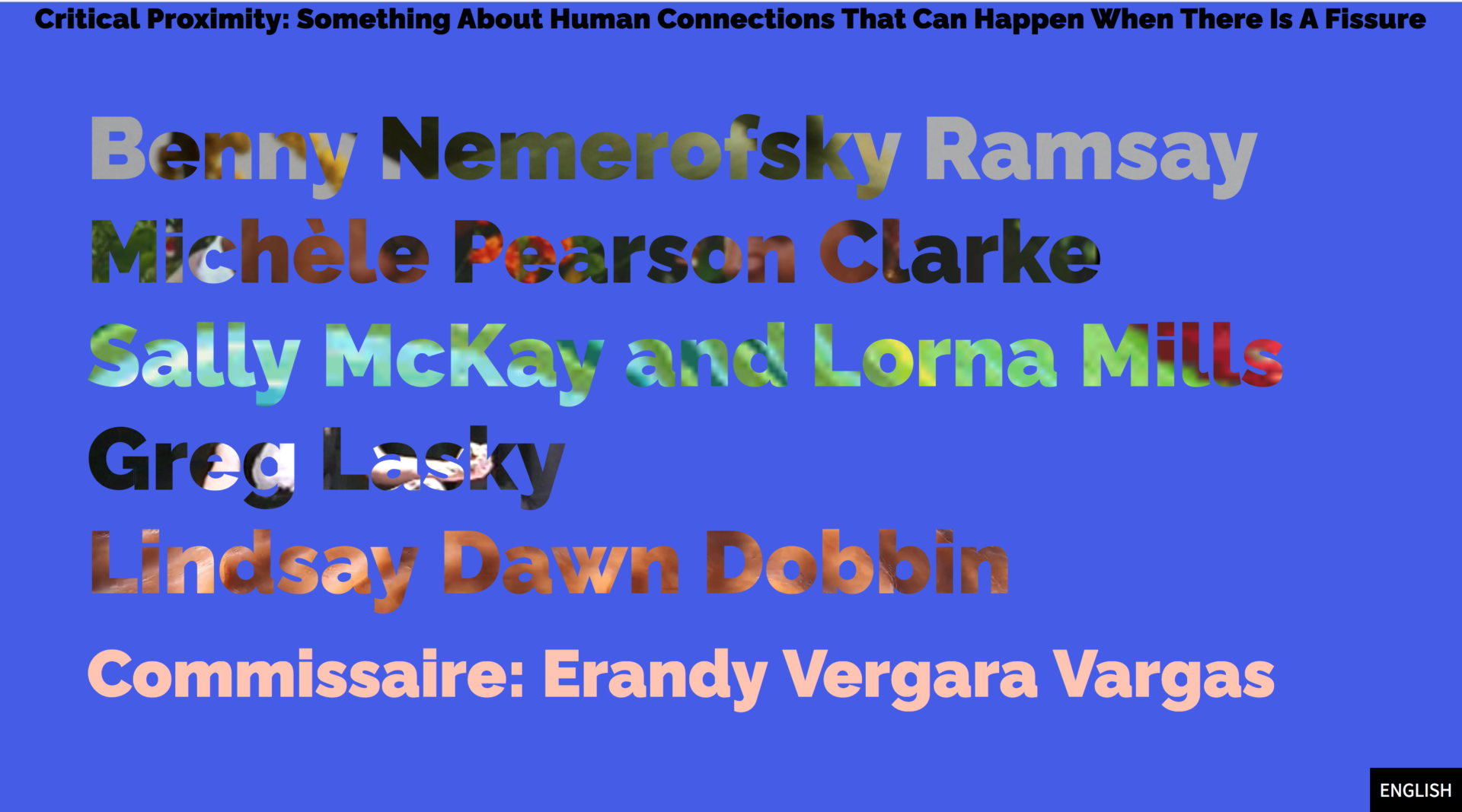

This show is personal too because it relates to my emotional connection to the work of Lindsay Dawn Dobbin, Greg Lasky, Sally McKay and Lorna Mills, Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay, and Michèle Pearson Clarke. The selected artworks deal with intimacy and forms of rupture. Some works directly engage broken objects or relationships (Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay’s Fragments of Rosalie and Michèle Pearson Clarke’s Handmade Mountain). One is inspired by pandemic grief (Sally McKay and Lorna Mills’ Boost Presume I’m Gonna Breathe Grieved). One conveys difficult emotions made common in the pandemic (Greg Lasky’s Untitled). Still another evokes the mental space opened after a storm, when we reach a new state and accept what is—ahead and around us (Lindsay Dawn Dobbin’s Arrival).

Benny Nemerofsky Ramsay’s Fragments of Rosalie (2021) consists of three photographs and audio guides accompanying each image. Benny rearranged the broken pieces of ceramic to create new objects that come into dialogue with three hand-made postcards by Rosalie Goodman Namer, the artist’s maternal grandmother, a prolific ceramic artist in Montreal. An intimate connection existed between these two artists. Benny mentioned creating something new out of broken pieces of pottery his grandmother had made when I first discussed the exhibit. I felt an immediate connection with keeping broken objects as an attachment with his grandmother and resistance to letting go. His piece tackles a fundamental part of our experience linked to objects that have stories, people, and emotions attached to them. Objects stop being material objects in the world and become memories involving senses like smell, touch, movement. Together, Rosalie’s pottery and hand-made postcards, and Benny’s engagement with them, brings a multidimensional, sensorial experience of love and closeness with one another. I think of my little treasures, all broken objects kept close. Even if stored at the bottom of a drawer, they are there, placeholders of my love no longer with a place to go. Benny invites us to delve into the intimacy he and Rosalie shared, which transcended age and remained beyond her passing.

Michèle Pearson Clarke’s Handmade Mountain (2019) also engages with rupture. She created this piece when she divorced her long-standing partner. In this video, close friends of the queer ex-couple express how they felt about the news. They talk about the struggles for same-sex marriage rights, the artist’s struggle to end a story, and the feeling of failure for an entire community. This video gathers the voices, facial and body gestures, and the struggles of this community of close friends who come together to unpack the feelings around this breakup. These stories felt close to my story and the stories of many of my friends who struggled because the pandemic forces us to confront “being together” in a historical moment when the world is upside down. “Happy endings” might not lie in being together but being apart. It is a powerful premise to engage with breakups.

Sally McKay and Lorna Mills’ Boost Presume I’m Gonna Breathe Grieved (2021) is a GIF artwork originally commissioned by Rea McNamara for Hyperallergic and the Emily H. Tremaine Foundation. The humor that is characteristic of web culture and these GIF pioneers welcomes us to a scrolling page with a “Click Me! Please! Please!” button leading us to listen to a fine selection of 1970s AM radio soundtracks. I laughed when I first listened to the Carpenters’ lamenting Ticket to Ride. Yet, as I scroll down, my laughter turned sour with the mixture of familiar images during the global pandemic, ecological disaster, and pure emotions of grief: hand-drawn and illustrated animations of an eternal rain, trees, and rivers, followed by digital images of moving skies, forests, mountains, fractured landscapes, forest fires. These take rounded forms. By breaking with the photographic rectangle, the images center our attention on changing and chaotic landscapes. Together, these formal elements create a sense of theatricality. I see familiar feelings and emotions: Fire, fire! Shit!, viruses, hands, touching anxiety; scenes of a road ahead seen from a moving car, mountain, eagle views, and hordes of animals running away, hurried, every woman for herself! Tears falling, but there is no escape. Who hasn’t felt this way, some way or another, in the past year?

Along these lines is Greg Lasky’s video, which I named Untitled (unknown year). I first saw this video around twenty years ago, when I attended a workshop with video artist and filmmaker Ximena Cuevas at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City. I was shocked, yet I connected with the cathartic screams that expand and contract in the video’s editing. When I selected pieces for this show, I kept thinking about my breaking points: the daily news, the coronavirus, social distancing, local lockdown measures, personal issues, relationships and losses. We all have moments where we only want to scream our lungs out without explanation, commentary, apology, or searching for anything from anyone. I contacted Ximena Cuevas because she received a copy of Untitled after she delivered an artist talk. A young man gave her a cassette and ran away. Even after all these years, this piece stuck with me. I thank Ximena Cuevas for sharing a copy of the work.

Lindsay Dawn Dobbin’s Arrival (2015-2021) is the result of the artist’s six-hour performance at the Bay of Fundy, known for extremely high tides. Water levels rise and fall by as much as 16 meters every day as one hundred billion tons of seawater crash into the shore. In August of 2014, when Lindsay Dawn Dobbin’s performance Drumming the Tide took place, the tides were at their peak in a 28-year cycle. The artist struck their handmade drum each time the moving tide met their body, and took a step forward toward the shore. They repeated this process for six hours, walking and drumming in the tide, until their body was carried to shore, submerged to the neck. I listened to the sound piece a long time ago and the powerful soundtrack stayed with me. While the work contrasts with the more cathartic pieces, the sound of slowness makes me think about arrival, not as an end in itself, but as a process and embodied experience with our surroundings, vast and open like the long performance that led to this audio work.

On Critical Proximity

As I said, I don’t share personal things online. My private life and feelings are nobody’s business. When I need to, I share with my family and close friends. In professional contexts, I share when I respectfully disagree—that doesn’t always go well. For the last decade, I’ve thought productive things happen in a fissure, when our connections and relationships don’t work, when we can’t connect, and when our connection with other people results in a shortcut. Oppressive structures affect us profoundly and personally. In my dissertation I formulated critical proximity as productive moments of disconnection that have at their basis a closeness. Some pieces invite spectators to physically get close to the works and interact with them. Others involve tactile contact. And still others explore metaphorical forms of closeness or distance between spectators and the work (or people represented in the work). Critical proximity is critical because it incites reflection on the interaction between the spectators and the artwork; proximity because its structure and aesthetics are felt closely, to erode the sense of distance and detachment between the self and Other. Set in opposition to the ideal of “critical distance” in Art History, critical proximity is a reflective means to defy ethics centered around the first-person and a detached view on technologies. In this exhibition, I revisit critical proximity to engage with our closeness to objects and subjects through artworks that incite difficult emotions such as sadness, grief, anxiety, and fear in the pandemic. This selection of contemporary artworks is a personal invitation to share intimate objects, feelings and experiences, to reflect on what has happened and what is yet to happen.